by Written by Ryan Salm and Sylas Wright in Arts, Features, Ski & Ride 2021

Beads of sweat emerge on my forehead as I maneuver around a 2,200-degree forge, careful not to step between glowing steel and hardened blacksmiths working in perfect unison. Torches hiss and sparks fly as piercing clanks of metal reverberate between walls lined with racks of hammers and tongs.

The busy scene is reminiscent of something straight out of medieval times, but it’s just an average day at Mountain Forge in Truckee.

“It really is an art form, and it’s kind of a lost art form because you can’t find hand-forged steel work like these guys do,” Mark Tanner, owner of the eponymous construction company, says of the Mountain Forge staff and the ancient craft they deftly employ.

While the practice of bending and shaping molten-hot metal has existed for thousands of years, professional blacksmiths today are a relatively rare breed. That is not to say the work they perform is obsolete.

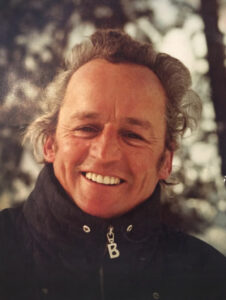

MOUNTAIN FORGE FOUNDER HANS STANDTEINER, COURTESY PHOTO

To the contrary, metal forging is highly sought after, particularly in the Tahoe region, where custom housing projects often call for intricate metal gates or ornamental touches on anything from fireplaces to railings to kitchen hoods—all of which, as Tanner points out, “are built to stand the test of time.”

But the story of Mountain Forge is not just about pounding and moving metal. It’s about an infectiously fun-loving Austrian immigrant who—like so many others over the years—came to Tahoe for the skiing and never left.

It’s about Hans Standteiner, a legendary figure who left an indelible mark in his 50 years in Tahoe, coaching up world-class ski racers and carving out a successful business executing an old-world trade at the nadir of its existence.

Standteiner’s impact both on the mountain and in the forge are still unfolding today, from the blacksmithing and skiing talents of his family to the entire community that he so warmly embraced. While his passing in 2019 was mourned by many, Standteiner’s legacy lives on through the passion and prowess he instilled in the next generation—and the timeless, functional art that Mountain Forge continues to create a half century after its founding.

AN AGE-OLD CRAFT

Metal forging is among the oldest trades on earth, with a dagger dating to 1350 B.C. providing the earliest evidence of man’s ability to shape metal, according to Forge magazine.

Although the weapon was discovered in Egypt, it was likely the product of a Hittite tradesman, as the ancient civilization is believed to have invented the process of forging and tempering iron ore. When the Hittites were scattered around 1200 B.C., however, so too was their knowledge of basic iron work, which they had guarded with secrecy.

During the Iron Age, a process to make wrought iron was developed by reducing natural iron ore with heat. The resulting product was used to make simple tools that proved much stronger and sharper than stone.

By the Middle Ages blacksmithing had become an essential profession, with each town enlisting its own resident smith capable of churning out various tools, household objects, weapons and armor. It was during this time that the surname Smith—the most common last name in most English-speaking countries to this day—was popularized.

Medieval blacksmithing techniques continued through the mid-nineteenth century, when the demand for metal forging decreased as the Industrial Era brought a cultural shift centered around machinery and mass production. As a result, many blacksmiths became farriers or found work in the early automobile industry.

While architectural ironwork was in demand in the early twentieth century, blacksmithing became a nearly extinct profession from the Great Depression until about 1970, when decorative metalwork came back into fashion.

THE START OF A STANDTEINER TRADITION

Johann (Hans) Standteiner was born on March 13, 1930, in the scenic mountain town of Bad Gastein, Austria. During the privation period that followed World War II, his parents sent him to live with relatives on a farm where food was more abundant. On his daily walk to school, the young Standteiner passed a blacksmith shop that captured his imagination.

“He sort of grew up in a foster home and didn’t have a strong family connection to any sort of trade, but he did say that the blacksmith shop just looked fun,” says Standteiner’s son, Toni, who now runs Mountain Forge along with his wife Jennifer. “There was always cool stuff out front and flames and sparks and metal. So he went to four years of trade school and then he got all his testing done in Salzburg in 1949.

“But his true passion was always skiing.”

Indeed, like most kids who grew up in the Austrian Alps, Standteiner was a skier at heart, and after completing three years of ski instructor training, he set off to pursue a coaching career that initially brought him to Iran and Turkey.

Standteiner may have never moved to the United States had a friend not convinced him to come to Sugarbush Resort in Vermont, where he met an adventurous young woman named Alice Gray and fell in love. The couple married and honeymooned in Bariloche, Argentina, where Standteiner coached both the Argentinian national team and the Chilean team, which he led to the 1960 Olympics.

“When he came to Squaw to coach at the Winter Olympics in 1960, he looked around and said, ‘This looks just like Austria, but it’s in California,’” says Toni, whose father eventually accepted a coaching job at Sugar Bowl on Donner Summit in 1968.

After enduring a huge winter on the summit, where the Standteiners had to tunnel out from their Soda Springs home, the family moved down the hill to Olympic Valley the following summer. Around that time, Standteiner opened a blacksmith shop along the Truckee River between Olympic Valley and Tahoe City called Forge and Anvil, which later became Mountain Forge.

“He had the summers off, so he said, ‘I’ll make a coatrack,’ and then a friend wanted a coatrack, and then the business just grew from there,” says Toni.

AUSTRIAN FLARE

In 1970, Standteiner took over the Squaw Valley Ski School along with Stan Tomlinson. As he had done during previous coaching stints in the Midwest, Standteiner hired a team of Austrian ski instructors who doubled as musicians with a predilection for playing Austrian folk music.

As such, a weekly “Tyrolean Night” at Bar 1 featured lederhosen, yodeling and spirited dancing, with Standteiner—remembered for his outgoing personality and good-natured humor—at the center of the festivities.

Among the Austrian influences at the resort, Standteiner also brought in Ernst Hager, who took over the race team while his friend and countryman ran the ski school (Hager went on to coach the U.S. Ski Team from 1975–1985, and again from 1991–1996). The two Austrians worked with aspiring young ski racers while their wives, Alice and Linda, ran a daycare program out of the “Gingerbread House,” through which countless kids learned to ski.

Although Hager was in charge of the race team, Standteiner was an ever-present, positive force, setting challenging racecourses and always making a point of keeping the skiing fun.

“We believed in being personable with the kids, and motivated them by being funny and keeping it light,” Hager told Edie Thys Morgan for an article in Ski Racing magazine. “Kids loved Hans.”

Toni, who grew to be a talented ski racer along with his four siblings, fondly recalls his father’s tutelage both in the forge and on the slopes.

“The only time I recognized his accent was when we were on the ski hill. I think he reverted back to his Austrian roots,” Toni says with a laugh. “He was a good coach. Most of the way he taught is he didn’t do a whole lot of talking. He would demonstrate and then you were expected to keep your eyes open and watch what he was doing and learn that way.”

FORGING IN THE FAMILY

One thing for certain was that Standteiner never considered blacksmithing a full-time career. In the early days of his shop, it was only open in the summer months and always took a backseat to skiing, despite its reputation for producing quality work. In fact, it was only 15 years ago that Mountain Forge transitioned to full-time employment, around the same time it moved to its current location in Truckee off Industrial Way.

Nevertheless, from its start, Mountain Forge served as a community hub of sorts for many in the Tahoe area.

JESSE BUSHEY OF BUSHEY IRONWORKS, WHO APPRENTICED AT MOUNTAIN FORGE, AND BROTHER AARON AT THEIR KINGS BEACH SHOP, PHOTO BY RYAN SALM

“More than anything, people were drawn here because of Hans’ electric personality. Everyone wanted to do what he was doing,” says Jennifer. “It was his relationships with people that have become the backbone of this business. Once you come into Mountain Forge, you’re in the family.”

Jesse Bushey can attest to that. Founder of Bushey Ironworks in Kings Beach, the Vermont native moved to Tahoe in 2001 and landed a job at Mountain Forge, where the Standteiners took him under their wing.

“That’s kind of where I cut my teeth and learned the trade,” says Bushey, adding that the elder Standteiner, who was still working in the shop at the time, had an uncanny ability to connect with people. “I had the greatest respect for that guy. He was such an amazing person, just the way he interacted with so many people in our community. It was always really special talking to Hans because he took the time to slow down his day and see how you were doing.”

Naturally, both of Standteiner’s sons gravitated toward the forge, with both Toni and his older brother Hansi—also a world-class ski racer along with sisters Barbara and Heidi—working in the shop from an early age.

HANS STANDTEINER WITH THE MOUNTAIN FORGE CREW, COURTESY PHOTO

“The girls never showed any interest,” Toni says of his three sisters, “but it’s not to say that they couldn’t. We’ve had a lot of female blacksmiths work for us here at our shop.”

As Standteiner neared retirement age, his sons took the torch at Mountain Forge, applying the skills and knowledge they gleaned from their father while continuing to grow the business. Hansi, who worked in the forge for years, recently retired.

Before diving full bore into blacksmithing, Toni—like three of his four siblings—left Tahoe to compete on the World Cup circuit as a member of the U.S. Ski Team. After five years of traveling on the World Cup, he went to the University of Colorado Boulder, where he won both an individual title and helped the Buffalos win the team title at the NCAA Championships. When not attacking gates, he worked toward a degree in architecture.

Looking back, Toni credits his World Cup travels for opening his eyes to the unique opportunity that his father’s business presented.

“I got exposed to the rest of the world and what a lot of people did for work, and I eventually thought, ‘Oh wow, blacksmithing is a pretty cool way to make a living,’” says Toni. “You get to be creative and work with your hands, and you get to work with a lot of really intelligent, creative people.”

As he returned from college and went to work at Mountain Forge with his father and brother—and eventually his wife—Toni started a family of his own, raising three children who remain avid ski racers at ages 17, 14 and 12 (they are among Standteiner’s 12 grandchildren). Toni also became a ski coach and continues to work in the winter months when not running the forge.

“The other day I went, ‘God, I’ve turned into my dad, man.’ I’m working in the metal shop and coaching a lot in the winter,” says Toni.

MOUNTAIN FORGE AT 50

While the daily grind at Mountain Forge may seem chaotic to an outside observer, the operation is highly efficient. Unlike most working environments where a hierarchy is in place, in the forge everyone does everything, from menial to most intricate.

Nearly as interesting as the work they create is the process of tooling up for their various projects. After the blacksmiths figure out what tools they need to best attack the job, they often make them from scratch.

“It may take upward of a week to make the necessary tongs, hammers, jigs, et cetera before they even begin to construct the actual project,” says Jennifer. “Most people have trouble grasping that.”

“It may take upward of a week to make the necessary tongs, hammers, jigs, et cetera before they even begin to construct the actual project,” says Jennifer. “Most people have trouble grasping that.”

That is why there are so many hammers and tongs lining the walls. Each has a purpose and was designed to pound or hold a specific piece of metal.

The process remains virtually the same as it was over a half century ago when Hans Standteiner first opened the forge. The difference in the late 1960s was that the need for blacksmiths was perhaps at an all-time low, whereas today the craft is experiencing a resurgence—evidenced by the increasing demand in the Tahoe area, as well as the popular History Channel show Forged in Fire, in which competing bladesmiths attempt to replicate weapons from the past.

Given its rich history and wealth of knowledge passed down through the generations, Mountain Forge is well positioned to ride this resurgence.

“Everyone in town knows that if you want custom high-end work, Mountain Forge is where you go,” says Tanner.

And it’s not just Standteiner offspring. The entire staff at Mountain Forge is highly trained and skilled. Take, for example, Matthew Christiano, who has worked at the forge for the past 15 years.

“He signed up to be on that show (Forged in Fire) and he ended up winning the whole thing,” says Toni. “One of the reasons he won is because, a lot of those guys on the show are just hobby bladesmiths or they just work on blades, but Matt is a true metalworker.

“He was able to adapt to any kind of forge and any kind of steel and still make a nice product. The guy he ended up beating was a really good bladesmith, and he said, ‘Man, you’re just an all-around good metalsmith.’”

A BRIGHT FUTURE

Back in the shop, the Mountain Forge crew moves smoothly but diligently throughout the space, station to station. After reviewing the project plans, each member of the team takes to his task with precision and safety in mind.

As Björn Pals works the heated coals of the forge, Dakota Myers pounds a slab of metal on an anvil. Cody Legan fine-tunes the petals of a metal flower, soon to be an ornamental flare on a high-end gate. All the while, Toni works the wire wheel.

MOUNTAIN FORGE BLACKSMITH BJÖRN PALS HAMMERS A GLOWING PIECE OF STEEL, PHOTO BY RYAN SALM

While they have the craft down to a science, the job is not without its dangers. Leather aprons and gloves are essential to protect the blacksmiths from shrapnel. Using the wrong tool can lead to overexertion and injury. Glowing-hot metal, open flames and sharp objects serve as constant reminders to exercise caution.

Toni once lost a finger to a band saw accident at Martis Camp, although he was lucky enough to have it sewn back on. His father wasn’t as fortunate, as he lost his entire pinky and most of his ring finger on his right hand while working on a hydroelectric project in Austria decades ago.

“He was an avid tennis player and a blacksmith and a skier, so he only had three fingers to hold onto a hammer and a tennis racket and a ski pole. But he made do,” says Toni. “He had these big fingers that looked like sausages and big arms, so he was able to grab onto a hammer with only three fingers. I’m sure there was some learning curve there and it took some time to build up the muscles, but he did it.”

It’s that tenacity and perseverance ingrained in Mountain Forge that has the business thriving more than 50 years after a charismatic Austrian brought an old-world craft to Tahoe. Fueled by a renewed demand for blacksmithing and a well-earned reputation as the best in the business, there’s no reason to believe that Tahoe’s oldest forge will not endure for another half century.

“I see [blacksmithing] on the rise,” says Toni, citing evidence from his California Blacksmith Association conferences. “I see a lot of enthusiasm with the younger generation to work with their hands. I think it’s kind of a knee-jerk reaction to the cubicle life and too much screen time. Whenever they see the shop, they always want to come in and swing a hammer.

“So I feel pretty good about the future of blacksmithing.”

For 20 years Ryan Salm has been pounding and sculpting a career as one of the premier photographers and writers in the Tahoe area, @ryansalmphotography. TQ editor Sylas Wright has long been intrigued by the ancient craft of blacksmithing. In fact, he sometimes watches multiple episodes in a row of Forged in Fire.